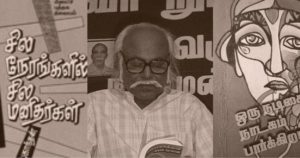

At the age of 14, writer Dilip Kumar became a wage earner for the family. He held a series of jobs in dry-cleaning and tailoring shops, and as sales clerk in textile shops, before he ended up as an employee at the Cre-A showroom in Royapettah. S. Ramakrishnan, the Tamil publisher, would serve as the budding writer’s mentor, but all this was much in the distant future.

Nearly a century ago, the maternal side of Dilip’s family migrated from Kutch, in Gujarat, to the southern city of Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu. Dilip was born into a well-to do business family in 1951. The premature death of this father changed everything.

For one, it slammed the doors of formal education shut on him. He could not study beyond the eighth grade. In one of the many early jobs he held, he also had to pick up his boss’s children from school each evening, a daily reminder of the education opportunity entirely lost to him, but there was no time to waste on self pity.

To keep formal learning alive, Dilip knew he would have to keep reading books on his own. As a teenager, he began his forays into Coimbatore’s Old Market where wastepaper dealers salvaged reading material, with some resale value, and send the rest of it, in tight bundles, to pulp mills.

The commerce of that wastepaper market would decide what books were accessible to Dilip. What was to be read, and in which language, he would have to figure everything out on his own. “I was greedy,” he recalls, “and I didn’t want to miss out on any of the best things, any language had to offer.”

English would help him get ahead in life. So yes, he bought Readers’ Digests. Perry Mason, the star attorney of Stanley Gardener’s courtroom novels, taught Dilip to “speak” English. There was Hindi, the most widely spoken Indian language; there was his own mother tongue Gujarati. In Tamil, which he spoke well, he read the popular magazines of the day.

One day, chanced upon a short story by Jayakanthan. Right away, he realized this writer was a standout. JK’s stories featured the working poor. “Why! The man actually writes about people like me,” says Dilip, recalling his amazement. He too wanted to write about such marginalized people, about himself. If visits to see his maternal relatives in Sowcarpet, Madras gave him a memorable cast of characters to work with , his working life too would supply him with experiences to write about once he acquired the language skills to craft stories.

In the Old Market, Dilip discovered the Russian Masters, “whose writing did not suffer for the indifferent translation into Tamil”, American novelists Hemingway and Steinbeck. His reputation as a reader grew in his hometown. So when any acquaintance had books to give away, they thought of him. “For instance, my friend’s bother had left behind a set of books. It could have been James Hadley Chase but it was J. Krishnamurthy’s works,” he says, marveling at his good fortune.

But these were one-offs. He continued to badger the radiwallahs, those wastepaper dealers at the market, with requests for obscure books and journals. This helped him connect with other readers of serious literature in his town. Where else would they go, the seekers of obscure journals, readers who didn’t have any real budget for books? Dilip’s informal network expanded. From a reading list, largely guided by chance, his world view widened.

And, as before, he continued to work. He was now in retail.

As part of his job as a clerk at a textile store, Dilip would pick up a piece of chalk and creatively advertise the owner’s brand of innerwear products on the pavement sandwich board. He used the titles of JK’s works to good effect. (Take for example: andharangam punidamanadhu. Literally translates to “intimacy is sacred.” It could also mean “your intimate parts are sacred.” So, please wear our undergarments.) Such literary puns would escape the notice of most passersby.

One day, a well-read bank employee walked in and asked to meet the creator of these chalkboard ads. He quizzed Dilip on what he had read thus far. He suggested some new authors including the books of the reclusive writer Choodamani Raghavan. (Not that many years later, Dilip had a chance to meet her in person. She would write an essay in support of his award-winning story Kadavu. After her death, Dilip would read all her short stories, some 300-400 of them, and anthologize her best work in a collection called “Cannon Ball Tree” but that is another story.)

So it went, his self-guided literary education.

And then, it happened. He saw an issue of a little magazine edited by none other than star-writer JK. It was slimmer, but more heavily-priced than the usual popular Tamil magazines at the tea kiosk. So what if he had to forgo tea for a few extra afternoons to save up for this magazine? Dilip soon began to wade through the unfamiliar waters of contemporary writing in Tamil with JK as his guide.

Decades later, when he spoke of this incident – a turning point in his life as it were to JK himself — the man said, “Why you could’ve watched a Tamil film instead!”

So much for meeting your idol, that distant beacon, in person!

He would “hear about a book, and then I’d read that book, and if it referenced another book, I’d track that one down.” And, sometimes, “It was just what was in the used-book bin because I was on a pretty tight budget.” He read everything from classics by Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, Cervantes, to novels like “Under the Volcano” by Malcolm Lowry, Doris Lessing’s “The Golden Notebook,” and works by Robert Stone. He read philosophy, poetry, history, biographies, memoirs and books like “Gandhi’s Truth” by Erik Erikson.